It was my very great pleasure today to discover that James Burke‘s groundbreaking TV series Connections and The Day the Universe Changed are all on YouTube.

Connections is more than 30 years old now — it was first broadcast in 1978 — and yet the way it weaves its threads through the history of science is still relevant to a contemporary audience. One thing I did notice, though, is how bleak his worries are, obviously an element of the Cold War mentality of the time.

Burke’s witty writing is a key part of the enjoyment, as this snippet from episode 2 shows:

I suppose Shakeaspeare and the travel agents have done more than anybody else to give us our Technicolor view of Elizabethan England, starring the Queen herself as a kind of swashbuckler in pearls. The fact is, about all she had time for was bookkeeping. When she took the place over in 1558, it was National Disaster Week. The money was worthless. There was no money! There was plague. The cities were packed and stinking.

Elizabeth appealed to the decent English middle class, with their healthy desire for prestige, power, fun and games, and cash. Soon, anybody who wanted to be anybody was on the make. And none more than that famous bunch of privateering seadogs led by Drake, Raleigh and Hawkins, who sailed the Atlantic looking for new American trade opportunities for England, setting up colonies, knocking off Spanish galleons — and doing it all with a kind of gutsy disregard for convention that we describe today as “criminal”.

I’ve often wanted to make programs like Burke’s. He gives hope to someone who, like him, has “a good face for radio”. I know that re-watching these old favourites will be important in many ways.

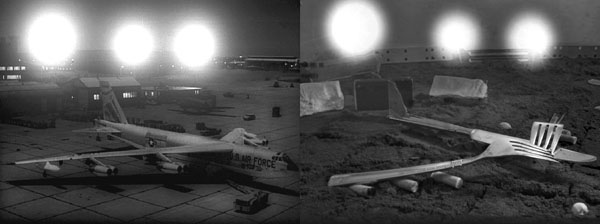

Bugger. The Space Age ended today.

Bugger. The Space Age ended today.