If the world was about to explode into a Total War lasting six years, would you know?

As I wrote back in 2007, TV documentaries about World War II cover the rise of Adolf Hitler in a few minutes. We forget that Hitler was head of the National Socialist Party from 1921, fully 12 years before he became Chancellor in 1933. It was another 6 years before the invasion of Poland.

What did it look like for people living it in real-time?

My guess is that for the vast majority of people the rise of Hitler had very little impact on day-to-day life — just as today the distant wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have virtually no discernible impact on my life in Sydney. Nor do the many minor changes to our laws which increase the powers of central government without any balancing increases in our own ability to hold that government accountable.

In the summer of 1932, a few politically-aware people sitting in sunny cafes might have discussed that odd Mr Hitler’s failed run for the presidency, but I doubt anyone would have seen it as heralding global war.

This is why I’m starting to find George Orwell’s diary intriguing.

Initially, as the Orwell Prize published the entries exactly 60 years after they were first written it was, to be honest, boring. Laughably so, in fact, as the meticulous journalist documented the day-to-day activities in his garden. On 30 November 1938, it was nothing more than: Two eggs.

But now, we’re only eleven days out from the German invasion of Poland. Thirteen days from Britain and France declaring war on Germany.

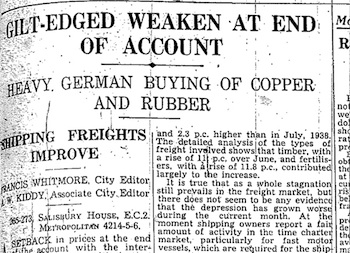

Orwell notes a Daily Telegraph report (pictured): “Germans are buying heavily in copper & rubber for immediate delivery, & price of rubber rising rapidly.”

Orwell’s journalistic eye could see the signs. Could ordinary citizens? Sure, gas masks were being distributed and air raid drills held, but did people believe them?

In 2007, did we believe John Howard’s “alert but not alarmed” scaremongering? Or didn’t we? And if not, but they did in 1939, what’s the difference?

I reckon Orwell’s diary will be an interesting read over the next 13 days.