I’ve decided that each weekend I’ll dig out an object or two from my more distant past and write about it. To kick things off, here’s a challenge which was originally created by the same chap who coined my name.

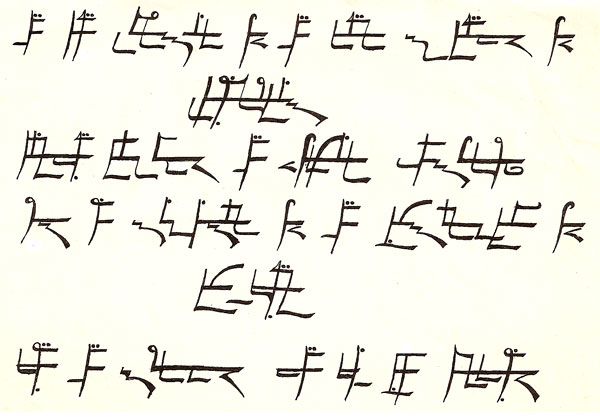

The text you can see in the image below (at least if you happen to be sighted) is in an unknown script. Your task is obvious, I think.

The only clues you have are that it’s a quote from a book by Ursula LeGuin and it’s nothing whatsoever to do with Tolkein.

Now originally I solved this in under 2 days, without the aid of computers or amphetamines. I reckon that in The Age of the Internet you can do better. I’ll negotiate a suitable prize for the first person who posts the solution.

@ryan: No, it has not been solved yet. It’ll be flagged rather heavily when it is. As the original post says, “I’ll negotiate a suitable prize for the first person who posts the solution.” That’ll depend to a large extend on who solves it, where they’re located, and how much of an arsehole they are. They more their motivation seem to be about prize-winning rather than joyous problem-solving, the smaller the prize will be.

Got dragged into a major project at work shortly after my last comment, but I haven’t forgotten this, or given up… pondering what other tools I may be able to bring to bear in decomposing the graphemes, at the moment.

Same here.

My motivation is “joyous problem solving” and my life is presently organized on a “duty first, pleasure next” basis, so there is not much time left for this challenge. However, I am still on board too.

I still can’t help thinking that people are over-complicating their approach to this. Some of the most basic cryptanalysis techniques should get you almost all of the way there. Particularly these days, where soft copies of the author’s books are available.

True. I just hadn’t managed to find them in a form I could apply some of those to. Besides, it felt like cheating, if the idea was to actually figure out the script. 🙂

@Joel: That said, after more than four years maybe a little bit of “cheating” is called for.

For anyone curious, the “cheating” method I was thinking of is simply doing a multi-line regular expression match based on matching up all of the spots where a word appears more than once in the script, based on distance-in-words. There aren’t many, but it also doesn’t take many to narrow the field down a *lot*, quite possibly to a single possibility.

However, (A) I don’t have access to an online copy of the books that would allow that level of detailed search, and (B) for me it is more fun to ponder the script, anyway. 🙂

Perhaps as something with little skill in phonetics, translations and cryptanalyses – I may be at an advantage by, as you say, keeping things simple.

I had started to just copy each of the “symbols” (again, please excuse my terminology) with the aim of converting them into a “sound” and then simply try and read the sentences.

The hard part would then simply be trying to work out where these “sounds” can appear on their own, or as a part of a word.

Having said that, I think Joel will probably nail it soon…

Would I be right in saying that where that “mid-line” connects the different “symbols” – we are looking at a word? Where they are not connected, and we see isolated “symbols”, theses are words like in, at, of and so forth?

@Alex Holsgrove: The technical terms you’re after are: “glyph” for what you call a “symbol” (ordinary people call them “letters” and “numbers” and “glyphs”, but this term covers every atom of writing); and “phoneme” (an individual unit of sound, which may be written using one glyph as in the English “k”, or two glyphs such as the English “ea”).

To answer your final question, the top line has eight words.

That was my count too (see my very first post). Thank you very much for confirming it.

A question that I keep running up against: if this is some form of transcription in a phonetic alphabet, is it transcribing the passage as spoken in AuE (Australian English), RP (Received Pronounciation / British English), GA (General American English), or based on a specific reading of it by someone?

UKL doesn’t provide a ‘standard’ pronunciation guide, specifically because she believes that the names should sound like whatever the reader reads them as (or something to that effect, I found it buried in some comments on her website).

The other half the fun seems to be that there were major changes to IPA in 1989, so even if it *is* based on the IPA, it wouldn’t necessarily be written out with the same symbols today. Or it may not be at all and I’m just barking up the wrong tree…

Line 1 word 8 continues to give me fits, because assuming that the first grapheme maps to either ‘s’ or ‘ʃ’, I cannot come up with any phoneme that both forms a real word *and* has an IPA glyph even remotely close to the one in the image.

@Joel: Well, we were living in Adelaide at the time and the local accent for us private-school types is closer to RP than anything else.

HERE IS THE BIGGEST CLUE OF ALL: Note that in line 1 the word at word 8 also occurs at word 4. And it’s one of the most common words in the English language. And I’m almost entirely sure that it doesn’t begin with either ‘s’ or ‘ʃ’. There is nothing in this script that could be seen as a visual echo of IPA glyphs.

@Stilgherrian: in my August post I had said that L1W4 appears four times, assuming L1W4 = L1W8, that you confirmed, and also that L1W4 = L4W4 = L4W7, which I take for confirmed as well. You also said that it is a very common word, which is compatible with my guess that it is a preposition (or possibly the verb “is”). I don’t think it is an article: it appears before L4W5, which I believe to be an instance of the same word as L1W1 (in spite of a very small difference in the initial stroke) and is also a frequent word. So I take L4W4 L4W5 to mean something like “Of the”, “is a”, “on a”, “Of my” or similar: “the of” “a is” and the like are probably out of question 🙂

In fact, for me, the RP clue is bigger that L1W4 = L1W8. Thank you very much for it, but please, please, please no more clues. It’s Friday morning now up above here (as opposed to Down Under). Please give me a weekend before further spoilers. 🙂

@dario: It’s a deal. No more clues for a while. Besides, to provide more clue than those already in the mix would require me remembering the entire solution. 😉 Have fun, folks!

I think I have it

… and in retrospect, it was “real beginner-grade material”, as Stil posted in October 2008. In fact, after a couple of hours before my own first comment in August, I needed only last Sunday and some more hours yesterday night to break it. I didn’t work on it in the meantime. However, it was clear that Stil was growing impatient (after 66 months!) and he was giving away too many clues. So finally I decided to test my initial hypothesis and it proved right at the first try.

Well, something is still missing from the picture. I could not identify the source work. Googling the last sentence, which is a motto, I found video games and other universes apparently not related to Ursula K. Le Guin. Since the script is a phonetic representation of English, I know how to pronounce but I cannot retrieve the original spelling of three words: two are fictional place names and the third is a generic classifier for one of them (as if they were “Australia”, “New South Wales” and “Commonwealth”). In my solution text I have used plausible spellings for them, in brackets. The challenge text is very short (110 characters) and it doesn’t cover all sounds of English. The internal structure of the script enables me to figure out how some of the missing sounds would be represented, but unfortunately not all (I was too optimistic in August.) There are also other minor doubts.

I am confident, however, that what I’m posting here is a correct solution, and I claim the prize.

@dario: Well, Sir, you have it! Congratulations! And to save people having to click through, here’s your image of the solution.

I must now confess that I seem to have led everyone down the wrong path. This is not the work of Ursula K Le Guin at all! It’s actually a document of some sort related to the fantasy universe of Danny, the guy who developed the script!

The place names Yocentro (as you’ve styled it, but I think Danny transcribed it differently in the Roman alphabet) and Rothmile trigger memories of a sandy desert planet. The well-wishing of “May the Sands be with you always” fits too.

I haven’t been in touch with Danny for years, but I’ve just emailed him to see if he can provide any missing pieces. But it was more than 30 years ago…

All that said, I do remember seeing and handling a document written in this script that was a Le Guin quote. I just gave you all the wrong document. Apologies!

On more practical matters, dario, “I’ll negotiate a suitable prize for the first person who posts the solution,” I said. I’ll email you privately about that tomorrow Sydney time.

That plus the “not a calligraphic variant of IPA” would explain the utter lack of success I was having (I hadn’t gotten around to beating on it further after the ‘it is not any variant of IPA or related phonetic language’ hint).

I would argue that a script that has no particular relationship to any common phonetic alphabet does qualify as encrypted (apropos earlier discussion of where you cross from ‘transliterated’ to ‘encrypted’). That said, it is still a fairly pretty set of graphemes, and I’m still curious about the full glyph breakdown / rules of construction…

For example, what are the rules about the breaks in the midline? The word ‘Sands’, for example, would seem to disprove my original theory that they might represent syllabic breaks, but the only pattern I can really find to them looking at it right now is that they seem to often (always?) be associated with a phoneme that starts with an ‘s’ sound.

And similar questions remain about the dotting; two very visually similar characters (the second phoneme in each of the first two words of the last line) have what appear to be quite different sounds mapped to them, which as far as I know is fairly atypical of natural writing systems. Do you know/remember if there is a significance to this, or is it just that it happens to be a constructed system and that was how the creator felt like drawing them? 🙂

In 2008 I wrote

Observation 1. It could be a simple character substitution code given that at least two “scribbles” are repeated throughout the script – the first “scribble” and last “scribble” on the first line for instance. If this is the case the commonly used English character frequency of letters table starting ETANOISH… could be of use.

———————–

I can see now that an excellent starting point would be simple word substitution – with 5 “the” and 4 “of” in a set of 28 words with the strokes representing an indication of how each word should be pronounced…. I can find “th” in [Ro”th”mile]

Bob

One thing I can point out without having received Danny’s reply is that the glyphs are quite systematic in terms of how they map onto phonemes.

“Glyphs are quite systematic in terms of how they map onto phonemes”

Translation…

“Find an appropriate phonetic font and type the words above into a wordprocessor” ?

I have been searching the 1 million 600 thousand “phonetic fonts” results from Google and even image searched for “phonetic font stilgherrian” where clues to the puzzle can be located possibly in terms of the name of the image file.

Having reached a solution we wait with baited breath for the ultimate key to the solution and whether or not Rothmile is on the Sydney City Rail network (sigh).

PS Rothschild wasn’t the name of the banker. It was short for “The Shop of the Red Shield Company” established by Amshall Moses Bauer in 1743. Mr. Bauer’s son changed the family name to Rothschild after his father’s death.

Bob

You’d still have to type it in phonetically… if I get some time, I might sit down and try to transcribe the entire thing to IPA, just out of curiosity at what it would look like, and because it would then be possible to represent it as Unicode glyphs. If I do, I’ll be sure to post it.

Here is a hastily written narrative of my decipherment process. Let’s say it’s a first draft of the full report I’ll hopefully be able to write. I have many more observations, charts to clarify many points, and so on. I haven’t just got the time to put them together right now.

When I learned of the challenge at the end of August, all hints pointed to a phonetic writing system for English (I did mention Deseret and Shavian in my first comment), so I started from there, working by the book: I broke up the challenge text (henceforth: the Document) into words, the words into characters, produced fig. 1, and, based on known facts about word freqency in English, I immediately identified three words: “the” and “of”, which I mentioned, and the single-letter L4W2, which had to be the article “a”, the most frequent English single-sound word. In cryptography jargon, such clues are called “cribs”. Then, let me quote myself:

When I wrote this I wanted to state facts. I didn’t want to share my wild guesses, but I already had an idea in mind: all vowels of my cribs were extended positives, the two consonants were strict negatives. What if the positives represented vowels and the negatives represented consonants? In that case the odd behavior of those glyphs with respect to the midline would have a fascinating explanation: the midline represented voice! Vowels, i.e. positives, are always voiced,

as well as sonorant consonants (the extended negatives!), while plosives, fricatives and affricates, the consonants that in English come in voiceless/voiced pairs, had to be represented by the strict negatives, which appeared in the Document both with and without a midline segment above them. If this was true, it wasn’t simply like Shavian, were the glyphs representing voiced consonants are flipped versions of the ones representing voiceless ones. In this script, voice was really written down with separate penstrokes of its own, as in some kind of spectrogram!

(In the following, I write IPA symbols between slashes, as /hɪə/, both to represent phonemes and to represent their corresponding script letters as I decipher them. I know this is against common IPA usage and I hope this causes no confusion.)

The hypothesis had to be verified. Of the two crib consonants, L1W4.2, the voiced final /v/ of “of” had indeed a “blue” segment above it, and this would imply that L3W4.1 represented /f/, its voiceless counterpart, but the other crib consonant, L1W1.1, the initial /ð/ of “the”, was also voiced, but had no segment above it! The whole construction, however, was too beautiful to be dismissed by that simple dash. Many writing systems have special exceptions for common words, so I didn’t consider my idea disproved, but I badly needed real data to see if actual English phoneme frequencies matched what I thought I was seeing in the Document. The ETANOISH sequence mentioned by Bob Bain is well known, but it holds for conventional spelling, and I considered it of little use here. Fortunately, one of the most authoritative living English phoneticians, Prof. John C. Wells, whose blog is in my RSS feed, had posted a piece completely written in IPA in June. It was probably long enough to extract significant phoneme occurrence statistics from it. I preferred starting from scratch and counting the phonemes myself, because Wells uses a standard transcription system I’m completely familiar with, while many articles that could be found on the web used somewhat different systems, different phoneme counts, were based on different varieties of English and would require more adaptation work (I was assuming that the Document represented an Australian variety rather similar to Wells’ British English, at least in phoneme distribution if not in realization… I hope I’m upsetting nobody with this sentence).

In any case the timeframe I could dedicate to this matter had expired. The challenge went into my TODO list with the lowest possible priority, and it stayed there for months. Last weekend, I pushed it to the top.

Not surprisingly, 12.38% of my sample consisted of the single phoneme /ə/. It was clear that in the Document no character was so frequent, but Wells’ is a radical transcription, where, for instance, “the” is transcribed either /ðə/ or /ði/ according to its pronunciation. If Danny, the inventor of the script I was deciphering, wanted to keep the same spelling for the same word in all positions, he might have used /ði/ throughout, reducing the frequency of /ə/. Such an approach might also have explained the disturbing fact that the single vowel of L4W2, a candidate for the indefinite article, far from being the commonest, appeared only there. I still don’t know the reason: now, I think that that letter means “indefinite article, sometimes /ə/, sometimes /eɪ/”. In any case, the positives made up 43.09% of the Document, and 39.44% of the sample consisted of vowels. Not close, but not apart enough to disprove the theory. Maybe there were some positives which weren’t vowels. I know now that that was indeed the case: L1W2.1 appears three times, 2.73% of the Document, and represents /h/, not a vowel and not even a voiced sound. But it is a simple slash, it is somewhat outside of the system just as /h/ is a somewhat special sound, so it’s OK.

After /ə/, the commonest phonemes in the sample are, in order, /ntɪslkr/. I had to go for consonants, that is, in my hypothesis, negatives. The extended ones had to be sonorant consonants. In English there are seven of them: /m/, /n/, /ŋ/, /w/, /l/, /r/, /j/, and indeed I counted seven extended negatives, all scythe-shaped, one of them dotted, either with a sharp or a rounded angle where the “handle” met the “blade”, at three possible depth levels below the midline: 3 depths × 2 angle types + 1 dotted = 7! Some strict negatives, on the other side, were the handleless counterparts of those scythes (let them be “sickles”), while the one I had already identified as /v,f/ and /ð/ had a completely different shape. Wait! The latter were all fricatives… could the former be plosives? In that case, could the three depths correspond to the three places of articulation of English plosives? In that case, the scythe representing /n/ would be at the same depth of the sickle representing /d,t/ (with or without midline), and similarly /m/ with /b,p/ and /ŋ/ with /g,k/!

(if you feel confused, this chart might help). Frequencies showed where /n/ and /t/ are. They are at middepth. Labials tend to prefer initial positions, so they had to be the shallow scythes (/m/ and /w/) and sickles (/b,p/), which also showed this preference. The velars were at maximum depth, with a very conveniently final /ŋ/ at L3W4.6, which also showed that the nasals where the rounded scythes, so that /w/, /l/, /r/, /j/ had to be the sharp-angled ones, identifying the dotted one (L4W6.1) with /j/ (I think you all know that /j/ is the initial glide of “you” /juː/, and not the “j” of “Jew” /dʒuː/)

There was also a spatial metaphor in this: the closer to the lips a sound is articulated, the closer to the midline its glyph is written. How elegant!

At this point I had most consonants, and I understood why vowels came in strictly positive or in extended form. Since there are so many scythes and sickles which can be easily confused with each other, some of them cut the stems of the following vowel, some don’t, and this is a way to tell them apart, alongside with sharpness and depth. For example, the boomerang-shaped vowel L3W4.4 isn’t cut by the preceding /l/ (middepth sharp scythe) but a preceding /r/ (deep sharp scythe) cuts it at L5W1.2. There are three possibilities: cutting, overstriking and joining, as in L6W4, where a shallow sickle (a /b/) joins the vowel of the article /ði/. Hey, this is the verb to /bi/! (There are still problems with the choice of strict vs. extended form of vowels, see below.)

Some fricatives were still missing, notably /s/, the commonest of them. A natural candidate was the commonest of the still unidentified glyphs, L1W3.4. It also appeared in a ligature with /k/ at the beginning of L1W7, which then could be read as /skr?b?/. Hmmm. “scribes” /skraɪbz/ perhaps? Tempting. This would identify L1W2 as “high” /haɪ/, solving the problem of L1W2.1, and understanding the initial sequence of L2W1 as /kh/. (/k/ is usually a cutter, as in L1W3, but probably /h/ can’t be cut at all, or /kh/ is a special case. Also, /j/ cuts L4W6.2 but doesn’t cut L6W6.2. Maybe cutting is optional for such an easily identified letter, maybe there are rules we cannot derive from such a short text. Never mind.)

A small problem with reading L1W2 L1W3 as “nine scribes”, however, was that /z/ was not represented as in L4W1 and as it should be, as an /s/ below a midline segment, but with a somewhat abbreviated form, easily confused with a final /v/ (the difference is that in /v/ the glyph hovers below the midline, while in the abbreviated final /z/ it dangles from it. I still don’t know if such an abbreviated form is always optional or is restricted to the cases when /z/ is obviously a suffix (plural, third person, genitive…), but again, it’s not a big problem.

If you have followed me to this point, you are surely able to find out the vowels for yourself. I’ll list a couple of final remarks here:

1. L3W5 is “personage”. I’d pronounce that word /pɜːsənɪdʒ/, but the vowel values I found correspond to /pɜːsɒnædʒ/. This confirms what we had already observed, that vowel characters in this script are not precise phonetic representations. In particular, reduced vowel sounds are (often) written as the full vowel they etymologically come from, just like in conventional English spelling. This word is also the only occurrence of /dʒ,tʃ/. We don’t know how /ʒ,ʃ/ looks like, there are no occurrences in the Document, but /dʒ,tʃ/ is composed by the middepth sickle /d,t/ and a final curl. Maybe that final curl alone represents /ʒ,ʃ/.

2. The whole Document is obviously written in an r-dropping variety of English, as shown by L3W2 /rekɔːdz/ “records” (for /re-/ instead of /ri-/ see the vowel comment above). However, L3W1 is “hereby”, and after a unique first vowel that I interpret as /ɪə/ (and is not in extended form, for an unknown reason), there is an /r/ character: /hɪərbaɪ/. The /r/ would be read only before vowels, but Danny decided to write it always, so that the same word is always spelled the same. Also, I don’t know why /aɪ/ is dotted here (and in L5W1, “Rothmile”). Maybe because there is another stressed vowel in those words. I don’t know.

3. The final vowel of L4W6 is a bit strange. It could be unique, but I think it is an /ɔː/ as in L3W2 /rekɔːdz/ “records” (strictly positive) or in L6W7 /ɔːlwəz/ “always” (extended positive), so I read that word as /jəʊsentrɔː/ and transliterate it as “Yocentro” or “Yocentror” but I am really in doubt here.

Thank you very much for keeping up with me for such a long post, and may the Sands be with you always.

Dario

(an Italian mathematician by study, sysadmin by trade, amateur linguist by passion)

Dario,

Many congratulations on solving the challenge. I find these thing fascinating, even if I knew I never had much hope of solving it before anyone else (if ever!).

Your prize, whatever it may be, is very well deserved as you’ve clearly put a lot of time and effort into solving this.

Well done again.

@Stilgherrian – thank you for posting this challenge all those months ago. I found your site after seeing the google name blog post, and stumbled across this. I’ve kept a keen eye on the responses and I’m sure you’re probably rather relieved that it’s finally been solved! Do you think you’ll do anything else like this again? Many thanks.

Alex

Updates on vowels

Thank you for your congratulations.

I’ve looked at the vowels once again and I must conclude that I still don’t know much about them. All I can show you is my vowel chart: under each glyph I’ve put the words where it appears, in ordinary spelling, with the corresponding letters underlined. If a character appears in the Document both in short and long forms (previously I called them “strict” and “extended”), I’ve put them both. I believe they are variants of the same character, but I must confess that all my previous theories about them proved unsatisfactory. At the moment, I still don’t know when to use a short or a long form.

As you can test pronouncing those words yourself, vowel orthography is not strictly phonetic: let’s say that Danny made some concessions to ordinary spelling. In any case, at least six RP vowels don’t appear in the Document and I have no idea how to represent them: /ɑː/, /ʌ/, /ɔɪ/, /eə/, /ʊ/ and /ʊə/ (assuming that Danny did not distinguish between /i/ and /iː/, /u/ and /uː/. Otherwise /iː/ and /u/ are also missing).

There are many uncertainties, I’ve already mentioned some of them. Here, I’ll say only that perhaps, the /ɜː/ glyph in “personage” is only the extended form of the /e/ glyph in “citizen”. A hint that there could be some phonetic meaning to short and long forms?

@Joel: I hope the chart I posted helps you with your question about the vowels in “May the”. It was Danny’s game. While the structure of the consonant glyphs was immediately transparent to me, the same is not true for the vowels.

What is missing now is a consonant chart. I’ll leave it for my next post.

@Stilgherrian: I hope Danny answers your mail soon. I hope he can remember some of the missing bits. If somebody asked me about the secret scripts and languages I’ve invented in my youth, well, there were so many of them I’d be embarrassed… but something I do remember.

Cheers,

Dario

No, I’m not ignoring all your comments. I’ve been busy. I should get to this stuff tomorrow.

I’m curious to know of the prize if Dario or Stilgherrian would kindly share?

@Alex Holsgrove and @Dario: This is where I’m embarrassed to say that it completely slipped my mind. My excuse? Dario’s win happened at a time when I was busy, stressed and a tad short of cash. Well, I’ll fix that within the next 48 hours. Stand by!

I’ve finally sent Dario his prize!