[Update 30 July 2010: The conversation continues. Adam Schwab has written a response to this article.]

Two weeks ago in Crikey, Adam Schwab dismissed the National Broadband Network (NBN) as “a poll-driven economic disaster”. His “analysis” is so full of misunderstandings and straight-up mistakes that it’s hard to know whether he’s pushing a pre-election agenda, deliberately trolling or is just an ignorant arsehat.

In a recent piece for ABC Unleased I proposed three tests for the credibility of NBN analysis. Schwab fails all three. He thinks the NBN is an internet service provider (ISP). He wants it to deliver short-term commercial return on investment. And he doesn’t differentiate between needs now and a decade or two or three in the future.

The NBN replaces an ageing copper network with a new one based on optical fibre. Internet access is an obvious application, but it’s also about services from pay TV to security monitoring to health — and, indeed, to good old voice telephone if that’s all you want. An analysis that only considers internet access is missing a lot of potential revenue.

The whole point of public infrastructure is that it generates benefits for all, not just short-term commercial return for investors. Think interstate highways, schools, armies, hospitals, police. It’s what governments do. As Crikey reported last year, OECD modelling shows that savings of 0.5% to 1.5% in just four sectors — electricity, health, transport and education – would indirectly pay for a fibre-to-the-premises network in ten years.

Arguing that current internet speeds are fine for what people currently do is a tautology. If speeds weren’t OK for current activities, they wouldn’t be activities at all.

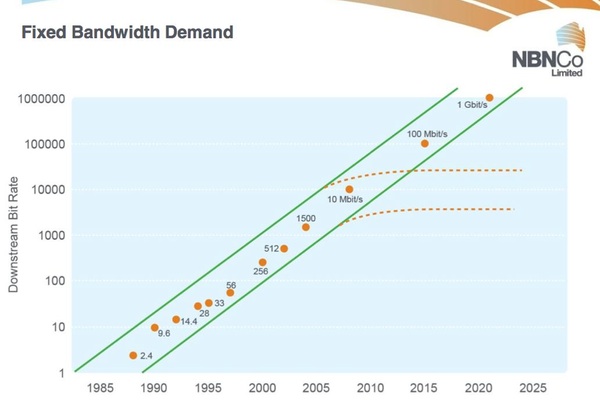

This graph shows the exponential growth in our typical demand for fixed-line internet speed since we first got dial-up modems in the 1980s. By 2015 the NBN’s initial 100Mb per second speed won’t be that stupid phrase “super-fast” any more, but merely average. Just twelve years from now we’ll want ten times that much, 1Gb per second.

Schwab is proposing that suddenly, today, this growth in demand will take the orange path and stop. Forever. Why would that happen?

All this is enough to dismiss Schwab’s nay-saying as irrelevant. But wait. There’s more…

Countering the argument “there may not be many uses for high speed broadband now, but like electricity or the phone, we need to build the infrastructure first”, Schwab claims “you either have electricity or you don’t, so the benefits of being connected to a power grid, even if unknown, had substantially more scope than the benefits of a faster internet service”. Rubbish.

It’s all about capacity. If you’ve only got 200 watts of power, you’ve got lighting and a radio but not heating, cooking, plentiful hot water or a plasma TV — and certainly not all those things at once. Similarly, a faster internet means more activities in parallel, not just one thing faster.

Schwab keeps repeating the cost of $43 billion, even though he knows “that was before the government was able to reach agreement with Telstra”. Even if it was still valid, that’s the total project cost. Some of it starts coming in as revenue from the NBN’s wholesale customers as the network rolls out. Misleading.

Rejecting potential benefits for eHealth, Schwab asserts without justification that “the main users of eHealth will be in rural areas” and reckons Rudd should’ve hired rural doctors instead. “You could probably get a few for $43 billion.” There’s that wrong number again, and he muddles a part of the equation (just health, and just rural health at that) with the whole shebang. Ignorant mistake, or deliberately disingenuous? And apparently our ageing urban population won’t benefit from being able to avoid traipsing across town, x-rays in hand, to see three different specialists.

Rejecting potential benefits for business such as videoconferencing, Schwab can’t think beyond “meetings”. “Meetings generate minimal economic benefits anyway,” he asserts. He clearly doesn’t understand the benefits of being able to throw together a work team to collaborate regardless of location globally, without time lost for travel. Carbon savings, anyone? Or of taking advantage of cloud computing.

“To achieve 100Mb the cost [to end users] is expected to [be] at least $120 per month,” asserts Schwab. Somebody had better tell the ISPs. Internode has 100Mb NBN plans starting from $59.95. Exetel’s 100Mb plan is $50 per month plus $0.75 per gigabyte download. They and others offer 25Mb or 50Mb speeds at even cheaper prices. Today.

Why is Schwab citing figures that anyone following this story knows are out of date?

And he repeats that old trope about not needing fibre because we’ll soon have magic 4G wireless broadband. Conveniently or ignorantly, he forgets that thanks to the Shannon-Hartley theorem wireless bandwidth is shared with everyone using the same cell tower, and that wireless suffers from interference and dead spots. It simply isn’t suitable for many applications.

I could go on.

But given all those errors, I’m guessing that Schwab’s real problem with the NBN isn’t technical but political. It’s a Labor project. Phrases like “testament to big government” and “remnants of the Rudd era” and “poll-driven economic disaster” are political rhetoric, not rational analysis. If he’s not trying to score political points, why mention Rudd at all? Why not just look at the project itself?

The clincher for that theory would be if he’d quoted an Opposition MP in support of his… oh hang on. He did.

[This article was originally written for Crikey on 15 July 2010, but was spiked when the federal election started to dominate the news, flooding it out. I’ve published it here on the day Schwab’s original article emerged from Crikey’s paywall.]

The technology for the NBN has been around for decades. All that’s been holding it back is cost and demand. I think both of these were met some time ago. We need a fibre network to continue to meet the demands even though they have surprisingly been able to squeeze so much capacity out of a copper network.

The other thing to remember is that these networks last for a long time. The copper network started going into the ground over 100 years ago. It has seen multiple changes of technology. I do not expect that anyone who installed the first cables to support telegraph and later manual telephones could have possible envisaged their use in mostly the same form for ADSL and internet connections. Fibre will also outlive the technologies that we are implementing. As we know we can already get up to 1 TB on a fibre pair. And though the cost of the terminals exclude their use in domestic houses, well the same was the case for other technologies now common. The price will come down over time and our ability to pay will go up.

Think interstate highways? I wasn’t aware we had any of these in Australia!

I worked out that even the high figure for the cost of the NBN would be approx 800km of all-singing all-dancing freeway. (Not even the distance between Melbourne and Sydney.)

Yet this project will reach 93% of the population not just one road. And unlike a freeway, it will be easier to upgrade the speed of the road just by upgrading the interchanges, not the whole road.

@yewenyi: The pace of improvement is something that’s very difficult to get one’s head around. By the time the last bits of fibre are being laid in 5 to 8 years from now, some of the initial locations will already be getting new endpoint technology. Maybe I need to add a fourth criterion for judging the credibility of the NBN analysis: an understanding that we’re building a living, evolving network, not a stating “thing”.

@mpesce: That’s “interstate” with a lower-case “i”.

@wolfcat: Just think of the difference between the two kinds of highway this way: One is optimised for delivering drugs, the other porn.

Infrastructure is a tricky thing to cost justify. Back in 1974 trying to cost justify an interractive screen based IT development system was impossible. The old system of the programmer writing the code longhand, someone punching it on a card, listing the result, bench checking and then submitting a “batch” run could be costed. The interractive system was expensive and there was no understanding of the savings that would flow from the changed way of developing/testing. No-one could forsee the possibilities of using a screen for interractive compile/test. Once implemented (on the basis of faith) it was impossible to go back. Try selling the “old” method today to any IT group.

Same for international telephone networks. Could not easily justify one to my employer (one of the big 4 banks). Based on the then current usage it was a no-goer. Once in the commercial possibilities opened up and suddenly the bank could not operate without it.

Once in, the NBN will open up apps and opportunities we cannot conceive of. Let us hope it has no download/upload quota.

I’ve just posted Adam Schwab’s response to this article. It’s probably appropriate to continue the conversation over there.